DECAYING INNER CITIES . . . FOOTBALL HOOLIGANISM . . .

A HARDLINE GOVERNMENT . . . IRA BOMBINGS. . . THE YORKSHIRE RIPPER . . . UNREST AT BRITISH LEYLAND . . . FIRE FIGHTERS ON STRIKE . . .

DEMONSTRATIONS ON THE STREETS. . . DISILLUSIONMENT . . .

HATE. . . ANGER. . . NEGATIVITY

YES, WE NEVER HAD IT SO GRIM. . . WELCOME TO 1977. . .

WELCOME TO . . .

THE STORY OF

AND BEYOND . . .

In the beginning . . .

when dinosaur bands ruled the earth, clogging the radio and T.V. airwaves with their own self importance and their long indulgent drum solos, a nascent revolution was slowly taking shape elsewhere. Tired of the times, the music, and bored to death with it all, a movement with a D.I.Y. attitude and a can-do spirit was gathering pace. Yes, the core of the idea may have begun in the city, but its roots were quick to spread, its message reaching out to every sleepy by-water and backwater and to every disaffected kid in town who had ever dreamed of doing something about it. The message was simple: Get yourself a guitar. Learn three cords. Now go start a band.

Hearing that message was like a call to arms to small town strummer, Pete Solo. Quick to act he set about a plan. He began to mobilise the troops.

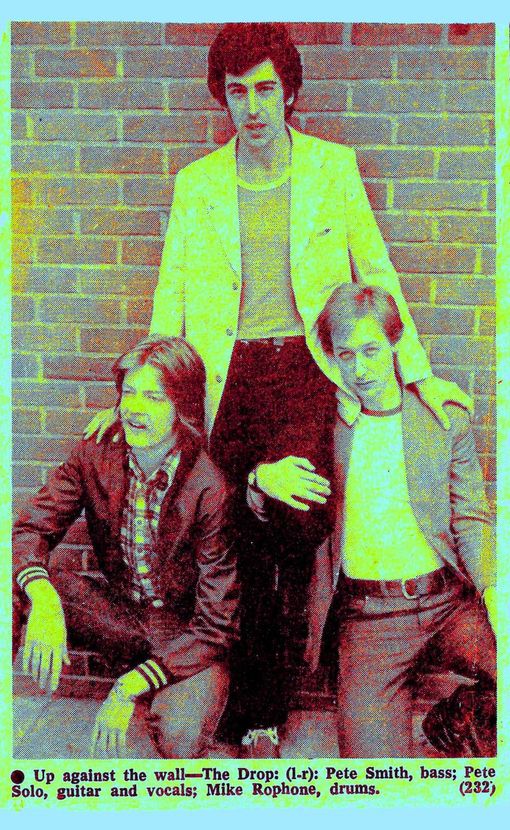

First to receive his call-up papers was ex- Grease Gun drummer, Mike Raphone, a well known face about town and someone with the key experience to provide the driving back beat that the band would need. With that sorted, and after bringing in Raphone’s brother, Chris on second guitar, the search went out for the next recruit, eventually finding Leeds bass-man, Pete Smith. With inclusion of the Northern bass-meister, the band was shaping up. They were ready to make their move.

The

next step . . .

was the look. For this was to be year zero – a rejection of all that had gone before. And if music was to receive an overhaul, then why not the fashions too. So while the old guard kept faith with their velvet loon pants and tea-clipper flares, the new ditched them in favour of straights, rocking combat shirts with the arms torn off, daubed with slogans and paint. Long hair was out too, cut short, spiked.

‘It was not so much evolution as revolution,’ comments Pete Solo. ‘And we were evangelical about it. As for money, or rather a lack of it, we didn’t let that hold us back either. We trawled the second hand clothes shops instead, buying and customising anything we found. Army surplus stores too. You’d always find something interesting and striking in places like that, cheap stuff from the war, ex military, things you could subvert and make your own. It was like we were preparing for battle ourselves. And in a way, we were – against the bands we viewed as dinosaurs. And we were coming for them – like the speeding meteor, hurtling to earth, to finish them off.’

Into battle . . .

with the Drop’s first gig. And as good fortune or good strategy would have it, they found themselves claiming the advantage of home ground – Bishop’s Stortford, a once prosperous market town in days of old, but by the mid seventies already a place like so many others – in decline, the victim of a flat-lining economy and the changing times. The upside of that recession was the earlier closure of the town’s maltings, and it’s subsequent and partial renovation and re-opening in the late 60’s and early 70’s as “Triad”, a centre for the arts, including the transformation of one of the huge defunct buildings into a rejuvenated venue for bands – bands that, back then, in the tail end days of folk and hippie rock, were in need of some rejuvenation themselves.

‘Those old bands just weren’t speaking for anyone back then,’ recalls Pete Solo. ‘Yes, they were accomplished, but really not saying anything new or relevant.’

Hardly surprising perhaps, given that in general the makers of that former music had tended to come from a different background to the others, a different class, one that was higher, but in being so did not best place them to comment on what was happening at that time: a period of socio-political change, and the expression of it through music: A new wave.

But that new wave was merely a ripple that night of the first gig. Bad luck blighted the affair, a power cut in the 300 capacity main hall meaning a last minute switch to a much smaller hall instead.

‘It didn’t exactly help,’ laughs Solo. ‘But in truth we were nowhere near ready. We need to go back and tighten things up. Become more organised – become what we wanted to be.’

In the next few months they did just that, returning to Triad once again, though slimmed down to lean three piece and hungry for revenge. They took it well, and with it three encores.

‘It was a triumphal return after the disappointment of the first gig,’ Solo adds. ‘We even came out of it with a profit – a bit of a disgrace in those days! Anyhow, it all went back into the band. That’s how it was then. The band was everything.’

As 1977 slipped into ‘78, The Drop continued to work hard, getting noticed, gaining publicity and garnering attention, no less than the night they were support band to U.K. top ten rockers, The Saints, who at that time were riding high at number seven in the charts. By then The Drop were riding high themselves, back to a four piece once again and restored to full strength by the inclusion of ex-Darlex member, guitarist Mick Galvin, after his defection from the well know local band.

‘I knew Mick well,’ Solo remembers. ‘We worked together in a studio in London when he was putting some of his own songs together. Then later we both played in Paris which was incredible. But that’s another story,’ he laughs.

(CLICK ON PETE SOLO IN HIS OWN WORDS TAB FOR "PARIS – THE INNOCENTS ABROAD TOUR")

But the fun was not to last as, soon after, Bassman, Pete Smith announced he was leaving for the States.

‘That was a real blow for us,’ comments Solo. ‘Pete had been with us from day one. He was irreplaceable. I suppose after that I knew things wouldn’t quite be the same again. That proved to be right.’

Ch. . Ch. . Ch. . Changes . . .

are inevitable with any band and The Drop proved to be no exception. By the year’s end it all began to fall apart, and with it the whole buzz and momentum of the new musical revolution in general as the money men and commercial giants came out of the woodwork, pouncing on and hijacking the erstwhile movement and turning the D.I. Y. genre into an acceptable, softer, homogenised blend. It was to be a slow death of the sub culture, though not so for the members of The Drop. Yes, they went their different ways, though that by no means meant their total separation, nor their capitulation, and certainly not their “retirement”.

‘We were too resilient for that – too determined just to slip off the radar,’ says Solo. ‘Besides, we loved what we were doing and in truth we didn’t know how to do much else.

Mike Raphone was the first to begin again, starting up and recruiting for his own outfit, Exposure, firstly bringing back Pete Solo on guitar, then bringing in talented new find, Graham Duthie on bass. With two respective female singers coming and going, but with the band itself making little headway, Raphone himself then left to begin elsewhere, leaving the door open to the equally hard hitting percussion man, Nick Patrick. And with the later addition of bass man, Johan Cloos, freeing up Duthie to switch to lead guitar, the new combo, Venice, stepped into the brand new decade of the 1980’s with a brand new sound, one that kept step with the times, though was fresh and unique too, making good use of Duthie’s strikingly distinctive style, coupled with his jangling, much favoured vintage Hofner Galaxie, the guitar making the band like no other. To capture that sound, studio time was duly booked and tracks were laid down at B.T.W. studio in London, produced by John Borthwick. A succession of gigs were commenced thereafter: pubs, clubs and the London circuit.

‘It proved to be a busy and gruelling time,’ comments Solo. ‘But I had no idea it would be life threatening too.’

The Good. The Bad. And the Dangerous . . . that was how the gigging scene was best described back then, especially with regards to the latter; it was not without risk. For although tastes in music had become less hardcore, toned down and softened, the general feeling of the people was anything but. Anger and unrest in the U.K. still prevailed, none more so than in London. And none more so than Brixton - the Railton Road – the so called “front line” from the famous song and scene of the infamous riots. It was to the epicentre of those troubles to which the band travelled on that fateful night in September 1981, the venue the equally infamous, Windsor Castle pub which was to be firebombed, though prior to its destruction, had already played host to many well know bands like Joe Strummer’s 101ers and later The Clash. That night however, Pete Solo and the band had little inkling of what was to come.

‘Actually, to begin with, it was a pretty good vibe – friendly even,’ recalls Solo. ‘Of course later, that was all to change.’

And change it did, but not before their set had ended and the band’s equipment was being loading into their van.

‘It was only then that the mood began to change and things began to kick off,’ adds Solo. ‘And when it did, it didn’t help that the van wouldn’t start. Not that we could have left at that stage anyway – Graham Duthie had forgotten his beloved Hofner guitar and had actually gone back inside the pub to get it. He wouldn’t leave without it! We laughed about that all the way back down the A10 – that and the fact the police had given us a push to get the van going. It was a crazy time.’

Alas that time was not to last. Eventually, and inevitably, as in most cases, after their period in the spotlight, the band would split, wiped out just like the dinosaurs who they’d wiped out before them, superseded by those who in turn would be wiped out themselves.

Thus the circle of music creativity turns. And turns again, leaving new bands to come along and carry the torch to highlight the days in which we live and live through. Long may that torch burn. And long may it be carried into the future.

Paul Foxley. By permission of M.B.E Music.

With thanks to Pete Solo.

For full Pete Solo interview, gallery, and press etc, click on buttons at top of website.